John Osland

Through his life on Lasqueti for 62 years, John Osland became a landmark. He seemed as much a part of Lasqueti as the land and the trees he admired. And in parting, left an ever-lasting gift to Lasqueti...

Storyteller, Lasqueti archivist, island historian, boatbuilder, sailor, lover of woodsman-philosopher Henry Thoreau, friend, John Osland left us on March 10. His love of Lasqueti is shown in his legacy. He also leaves us with memories of his broadcast-quality stories, delightful wit, fierce independence, and remarkable physical toughness.

John was born in Woonsocket, South Dakota, on Boxing Day 1918. “John Osland, no middle name. My parents couldn’t afford one.”

Just before the Second World War, John built an 18 foot sailboat in his parents’ backyard in Salem Oregon, and ran down the flooding Willamette and Columbia Rivers to the Pacific.

According to newspaper reports at the time, he figured that going to sea single-handed in his small boat would give him the quiet that he wanted to get some reading done. He headed down the wild coast of Oregon and California with a few charts, a large supply of books and a smaller supply of food. Within a couple of weeks he was declared "Lost at Sea". More likely, he was enjoying his reading, and was in no hurry to rejoin town life. "John is not lost at sea. He has Viking blood," said his dad.

His later plans of continuing his sailing down to Panama were scuppered by the Military Registration Board, who didn’t want military-aged men sailing out of US waters. So he and his 18 footer had to end their trip in San Diego, 1100 miles of open Pacific from the mouth of the Columbia.

After three years of the Second World War aboard US Coast Guard ships escorting military supply convoys from San Diego to the Philippines and from Australia to American-captured islands across the South Pacific, John keenly needed more quiet reading time. He attended the University of Oregon for a year, then came north to Lasqueti for the summer of 1948. He was hooked.

He found a piece of land where he could work his fields, walk among ancient trees, and climb to the top of the third highest point on Lasqueti. He could discuss books with his neighbour Archie Millicheap, and socialize with the Douglases. And he could soak up the stories, told by the old-timers and interspersed with Chinook words, that he could still vividly retell 60 years later.

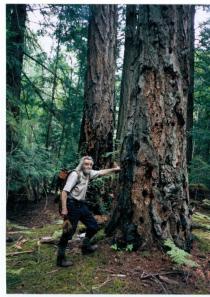

During his early years on Lasqueti, logging of the old-growth trees was going strong. With pressure from some neighbours, he signed a two-year logging contract and was glad at first of the dollars that it began to bring in. After the first summer, however, he had a change of heart. He wanted those massive old trees to be allowed to remain, without having to fall “in the name of the dollar” as he put it. Luck was on his side, and the second summer was too dry for much logging. When the logging company wanted to extend their contract, he refused. So John’s big trees have remained.

John cared deeply about public decisions which impacted Lasqueti. His Viking blood was known to enliven meetings if he felt that the long-term best interests of Lasqueti were not being upheld. Never using a powersaw, and never bringing a car to Lasqueti, he was skeptical of plans to bring “so-called development”. Responding to someone who wanted an improvement to the ferry service, he said “When I came here the boat came once a week, sometimes in the middle of the night, and we thought we were lucky!”

After 2 or 3 decades (depending who you asked) of hand-building, John’s 30 foot sailboat was launched in 1986. The effort paid off as John’s sailing and rowing of this 5 ton boat provided more than its fair share of stories for the next 20 years. The first shakedown cruise found John crossing the Gulf with insufficient ballast and a rising southeaster. The next morning, the good people of Hornby were delighted to find an ancient mariner with his boat high and dry, but undamaged, on a little patch of sand surrounded by rocks.

Despite, or perhaps because of, his remarkable life John never seemed to grow old. At age 90 he was building incredibly tall skinny ladders to enable himself to build a treehouse 40 feet up one of his cedars. And despite cataracts, he still rode his bike at speeds which terrified onlookers. When asked at 90 what his secret to fitness was, he replied “First, you’ve got to be poor!”

Leaving only his bicycle tracks along his grassy driveway, and trails for carrying bags of bark home on his back, John walked lightly on the land. He got immense pleasure from walking among his big firs; it was always a treat to do this with him. For the last twenty years John wanted to find a formal way to protect the Nature on his land after he was gone. “Too often Nature has to serve the almighty dollar.” He envisaged his land being a place where Nature could be left mostly undisturbed except for visits and walks by those “seeking the enjoyment of Nature.”

John left his land to the Island Trust Fund, to become a Nature Conservancy. It will take up to a year to complete the process, so there will be a public announcement when the land is open for public access. John hoped that the people of Lasqueti would enjoy it and care for it as carefully as he did. A remarkable legacy for a remarkable man.

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and to see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I wanted to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life… I learned this, at least by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected.” Henry Thoreau, 1854

A number of people gave John a hand over his later years, and particularly over the last two weeks of his life. You know who you are. Mike Mundy and Cindy Craven deserve special mention for over 20 years of assistance given whenever it was needed. To you all, in the words of John, “Thanks a million.”

Donald Gordon